What novelists should strive for (according to Ayn Rand)

Image created by A. L. Peck using Canva.

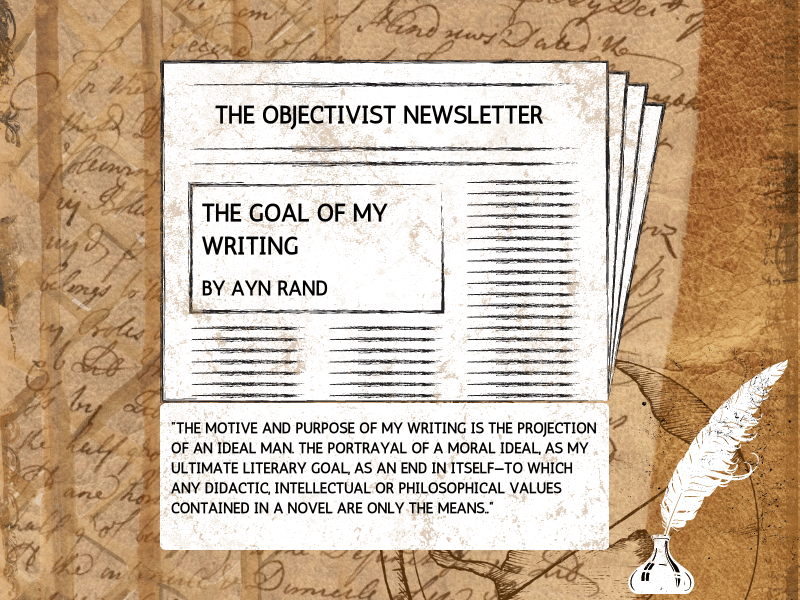

After writing Atlas Shrugged in 1957, Ayn Rand shifted her focus to nonfiction. From 1962-1965, Rand published a series of monthly newsletters in The Objectivist Newsletter, The Objectivist, and The Ayn Rand Letter.

Her articles covered a range of topics including the virtue of selflessness, capitalism, the dangers of censorship, a Q&A column called the "Intellectual Ammunition Department" where Rand and her colleagues responded to readers' questions on philosophy, and even book reviews (she greatly admired Victor Hugo).

All of her writings focused on the branch of philosophy she created, Objectivism (which advocates for reason, selfishness, and laissez-faire capitalism), and the main purpose of her newsletters was to provide readers with a philosophical framework. Many of her writings here later formed the content for her longer philosophical essays and books.

For a brief interlude…check out these articles for more insights + subscribe to my newsletter:

The ultimate aim of Rand’s writing

In one of her articles, "The Goal of My Writing," Rand describes the intention of her works and what it requires:

"The motive and purpose of my writing is the projection of an ideal man. The portrayal of a moral ideal, as my ultimate literary goal, as an end in itself—to which any didactic, intellectual or philosophical values contained in a novel are only the means."

Rand’s final aim is to show what humans are capable of achieving and to provide a moment of relief or inspiration for those on the path to self-actualization. She does this by presenting many of her protagonists at the peak of their abilities and describing the joy and satisfaction they experience upon realizing their goals.

The importance of subject matter

To create a compelling story, Rand considers what makes characters and events interesting and why. For her, this means looking at the most intelligent, virtuous, and heroic aspects of a person.

This is an uplifting perspective—she doesn’t dwell on negativity or the darker parts of humanity but instead believes these factors aren’t worth serious contemplation. Their only role is to act as a foil to highlight man’s capability. Fiction presents possibilities, why portray the negative?

This view was inspired by one of Aristotle’s ideals—conveying humans as they should be and are capable of being. She writes in her newsletter:

“It was Aristotle who said that fiction is of greater philosophical importance than history, because history represents things only as they are, while fiction represents them 'as they might be and ought to be'."

Thus, her stories revolve around her protagonists seeking self-actualization and her message is ultimately uplifting and inspiring.

Rand’s philosophical foundation

Rand believes that determining the most interesting aspects of people requires an ethical, moral, and philosophical framework. This framework provides both a code of values to guide the characters’ choices and actions as well as the conditions needed for the society the characters live in.

In Atlas Shrugged, her philosophy is:

“The concept of man as a heroic being, with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life, with productive achievement as his noblest activity, and reason as his only absolute."

To present the ideal man capable of achieving his highest potential, she needed to create a laissez-faire capitalist society that rewarded man for innovation and efficiencies. Essentially, philosophy and writing are inseparable.

What writing is not

It's important not to mistake the requirement for an ethical foundation with the idea that the goal of fiction is to teach ethics or otherwise. Rand states that portraying the “glory of man” is her only end goal and that everything else (i.e. advocating her philosophy or teaching her readers) is secondary.

She had a “desperate longing for the sight of human achievement,” and in her novel The Fountainhead she writes, “show me your achievement—and the knowledge will give me courage for mine.” The function of her writing isn’t to teach but to show.

Rand’s writing style

Style of writing is another important factor for Rand. Style is essentially how an author writes (i.e. clearly and concisely or lyrically and jumbled) and the elements he uses to achieve this, like word choice, tone, sentence structure, poetic devices, and narrative structure.

For Rand, unsurprisingly, in art and literature style is another means to an end—but it can't contradict the subject matter or the writer's ability. Why employ the skills of a great writer to portray a subject unworthy of contemplation or to describe a worthy subject but in a lowly manner? In her words, "there is no esthetic justification for the spectacle of Rembrandt's great artistic skill employed to portray a side of beef."

Further, if a writer does have a great ability, Rand considers it immoral for him to portray the bad and the ugly as ends. This is likely because Rand understands that a great writer can manipulate his readers or sway them to believe one thing over another. So he shouldn't use this ability to give credence to the negative aspects of humanity. Thus, style and subject must be aligned.

However, the choice to prioritize style over subject or vice versa depends on what the writer believes the aim of writing is. Since Rand intends to portray man as the highest being, the subject matter is more important than the style of writing.

For readers to understand what she conveys, she has to display this in a clear way—no non-linear plots, lyrical language with heavy metaphors and hyperbole. Her style is straightforward and the actions and characters speak for themselves. If readers are meant to take any message or value away, style must be secondary.