Imagination, empathy, and John Keats’ negative capability

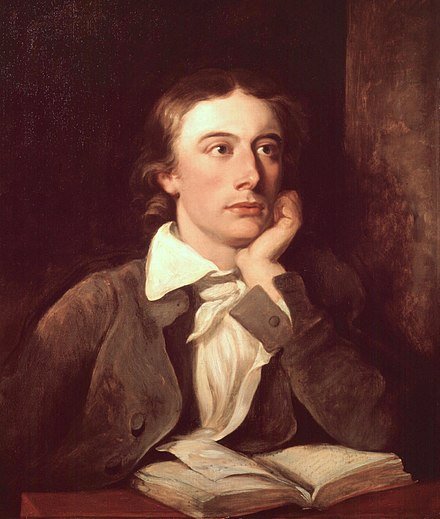

John Keats (1795 – 1821) was an English Romantic poet who’s best known for his odes, like “Ode to a Nightingale.” Despite a short life, dying at age 25 of tuberculosis, he contributed significantly to English literature.

One of Keats’ contributions was the idea of negative capability—that we can’t rationally understand particular experiences in life, so we should become comfortable living with their uncertainties:

“At once it struck me, what quality went to form a Man of Achievement especially in Literature & which Shakespeare possessed so enormously—I mean Negative Capability, that is when man is capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact & reason.” – Keats in a letter to his brothers from December 1817 (emphasis mine)

Instead, we can gain a deeper understanding of the world (and how to live in it) through imagination and empathy, which art, music, and literature are conducive to.

The inexplicable quality of living

There are elements of human experience that we can’t rationally understand—things like intuition, unconditional love, and religious experiences. Essentially, anything that makes us feel like we’re profoundly connected with the world.

Even Albert Einstein thought deeply about this. He called it a “cosmic religious feeling” and believed the ultimate goal of both art and science was to induce this feeling: “In my view, it is the most important function of art and science to awaken this feeling and keep it alive in those who are receptive to it.”

This is exactly what Romanticism* sought to do—to replicate and contemplate the sublime. The sublime is an extreme or overwhelming response to extraordinary sights or encounters, similar to a religious experience. Typically, the Romantics used nature (intense cliffs, storms, the sea) to evoke these feelings.

The idea is that through mixing extreme emotions (like awe, wonder, and terror), you can more deeply contemplate and feel comfortable with the interconnected nature of the world.

Imagination breeds transcendence and understanding

The reason we can’t rationally understand the cosmic religious feeling or the sublime is that our individual experience is a “sort of prison”:

“The individual feels the futility of human desires and aims and the sublimity and marvelous order which reveal themselves both in nature and in the world of thought. Individual existence impresses him as a sort of prison and he wants to experience the universe as a single significant whole.” – Albert Einstein

Instead, the Romantics (including Keats) advocated for using our imaginations to transcend ourselves. Imagination offers a temporary escape from the self. By envisioning the experiences of a character in a book, for instance, you can begin to understand a broader perspective.

Similarly, good art captures the essence of whatever it’s trying to convey (i.e. a particular emotion, idea, or experience). It allows whoever’s looking at, reading, or listening to it to forget themselves and become fully absorbed in those same feelings or experiences—making you more comfortable with new ideas.

Empathy is the key to imagination

However, empathy is required for imagination. The American poet Mary Oliver (1935 – 2019) even described empathy as the first step to negative capability:

“The second world—the world of literature—offered me, besides the pleasures of form, the sustentation of empathy (the first step of what Keats called negative capability) and I ran for it. I relaxed in it.”

By creating an emotional openness, empathy can foster a deep connection with the world and all forms of life within it. For Oliver, literature (and nature) was a way to experience life’s uncertainties and complexities:

“I stood willingly and gladly in the characters of everything—other people, trees, clouds. And this is what I learned: that the world’s otherness is antidote to confusion, that standing within this otherness—the beauty and the mystery of the world, out in the fields or deep inside books—can re-dignify the worst-stung heart.”

Mary Oliver with one of her dogs, photograph by Rachel Giese Brown

*Romanticism was an artistic, musical, and literary movement that originated in Europe in the late 18th century. It shifted away from the rationality and tradition of the Enlightenment and instead favored emotion, imagination, and innovation. Typical Romantic works focused on (and dramatized) nature and the individual self.